A Lady's Heart of Gold

A Lady's Heart of Gold

Narrated by Marian Hussey

Couldn't load pickup availability

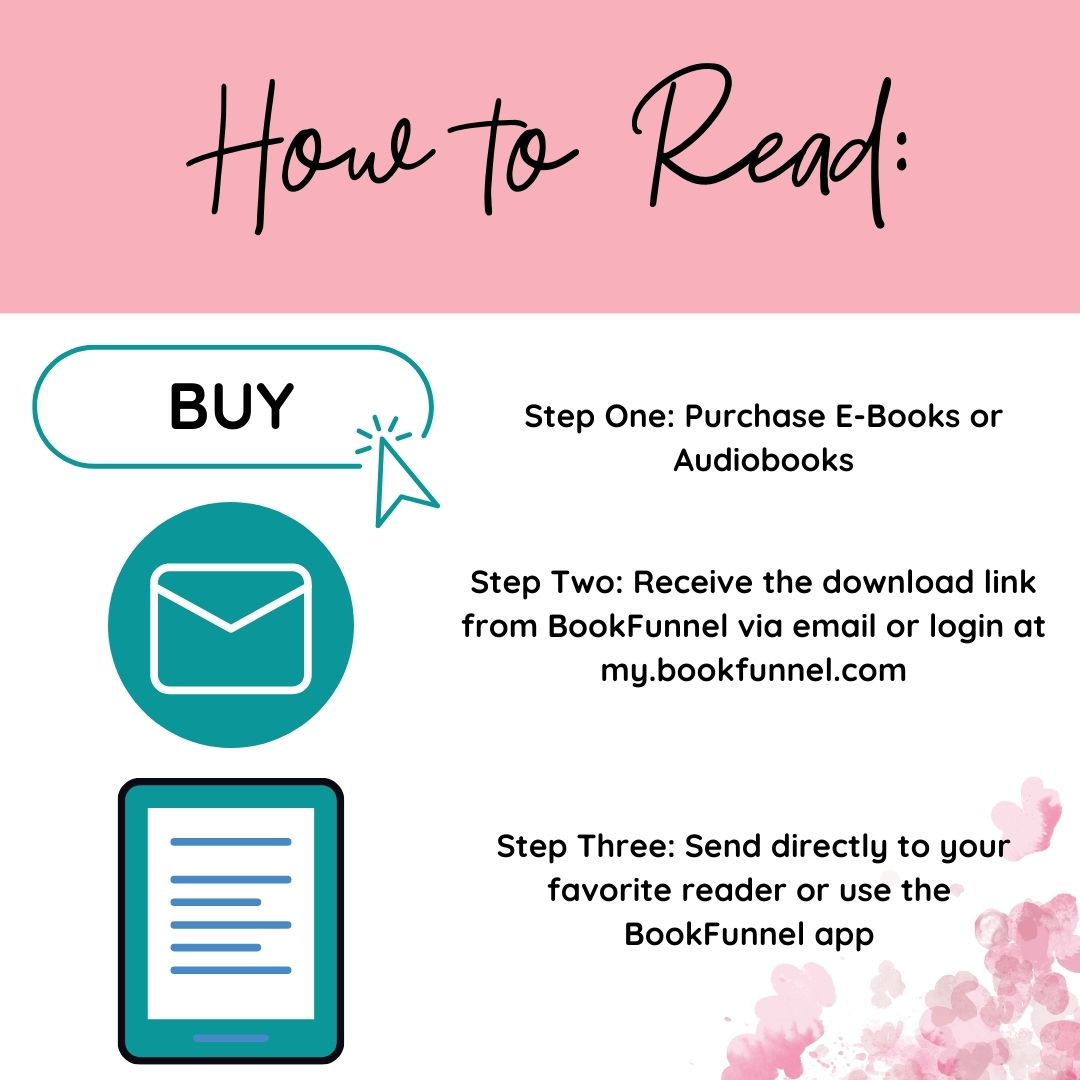

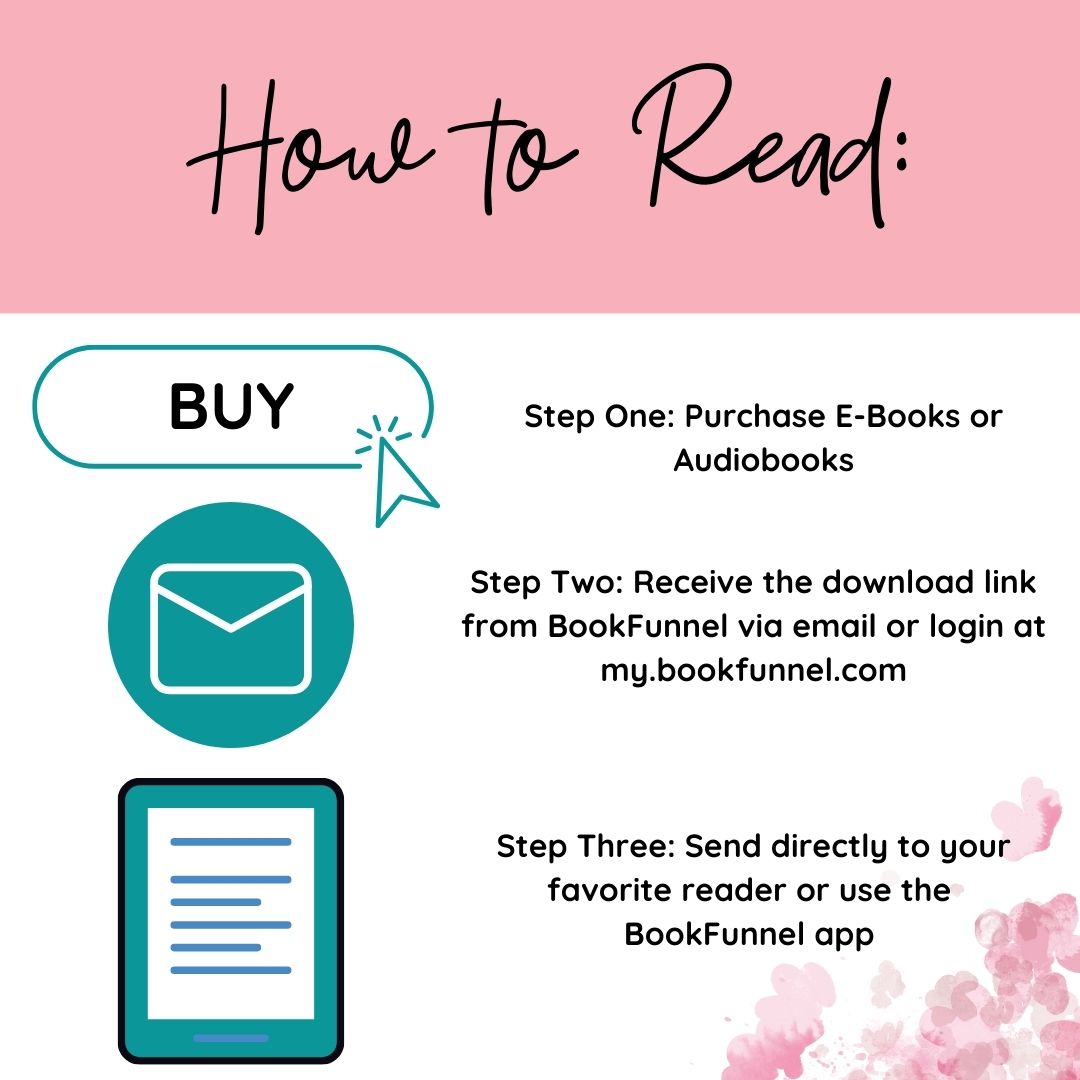

- Purchase the Audiobook Instantly

- Receive Download Link via Email

- Stream on BookFunnel or Download MP3 Audiofiles and Enjoy!

Main Tropes

- Cowboy Hero/POC Hero

- Culture Clash

- Victorian/Western

Synopsis

Synopsis

When a determined English newspaper woman arrives in the Arizona desert, she expects to find the lawless and the illiterate. Instead, she meets a well-spoken and handsome cowboy who's ready to prove to her there's more to the Territory than cattle and cacti.

English newspaper reporter Molly McKinney is determined to make a name for herself by writing about the wilds of the American West. After convincing her editor to take a chance on her idea, Molly travels to the United States looking for tales that will transport and inspire her readers. When she meets a quiet cowboy in the middle of Arizona Territory, she can sense that his story might be the most important of all—if only he’ll open up enough to tell it.

Eduardo “Ed” Byrd has worked at the KB Ranch for five years, making an honest living and trying to ignore his past. He’s one-quarter Cherokee, three-quarters Mexican-American, and entirely his own person. Light-hearted and hard-working, Ed keeps to himself and reserves his dreams for the privacy of his notebooks. When one meeting with the tenacious English woman rattles his mind and heart, Ed can’t help but wonder if he’s been playing things safe for too long.

A reporter’s natural curiosity spurs Molly to make her way to the ranch where Ed works, and she’s determined to find out what the cowboy is hiding beneath his gentle smiles. There’s more to Ed than he lets on, and when Molly starts to unravel his past, he realizes their story might only have a happy ending if he’s willing to risk more than just his heart.

This is the third novel in the Hearts of Arizona series. Each story is set in Arizona Territory and features a Victorian hero or heroine, with a mild heat level.

Intro to Chapter One

Intro to Chapter One

If the right combination of doors opened all at the same time, the noise from the presses in the basement traveled all the way to the rooftops of the publishing district. But since most people considered the click-clack and thrum of machinery deafening, the doors of The London Guardian all stayed firmly shut during business hours. Which made the fact that Molly McKinney could hear the editor-in-chief shouting inside his office while she remained in the waiting room quite a feat.

Molly kept her shoulders back, her chin up, and her gloved hands folded tightly over her portfolio of clippings. She made brief eye contact with Mr. Gilchrist’s secretary, who winced sympathetically when the editor’s voice rose still higher. Really, it was quite impossible to miss what he shouted at the half-dozen journalists inside the room with him.

“You’re all writing fluff that any street urchin’d do a better job reportin’.” Several words unfit for print followed as he continued to describe the quality of the stories the men had submitted. “We need somethin’ better. Somethin’ different. We’re fighting against cheap novels, sensational headlines, and you give me more stories about wharf-murders and society parties? We need stories better than that if we’re goin’ to capture our readers. We need somethin’ they come back for, week after week, that they can’t get anywhere else.”

Someone else in the room spoke, too low for Molly or the secretary—whose neck had disappeared into her shoulders—to hear. Whatever that person said, the editor didn’t like it.

“Get out of here! All of you, get out of here and bring me back something worth the paper and ink I waste on you!”

The first man out flung the door open and rushed through the room, clapping a hat on his head as he went, his face pale. The other five men who’d sat through that tongue lashing hurried out, too. Some of them red in the face, others white as sheets, but all looking as though they’d eaten something that disagreed with them.

The secretary stood and picked up a small notebook. She swallowed, then walked on shaky legs to the door. “M-M-Mr. Gilchrist?”

“What is it now?” he snarled.

Molly pulled her leather portfolio tight against her chest. The clock on the wall opposite showed the exact time she had scheduled her meeting with the editor. And while she had no intention of letting his temper get the better of her, an impatient man was unlikely to give her a fair interview.

“Your next appointment is here. A M-M-Miss McKinney?”

“The lady journalist?” He sounded as irritable as ever as he said, “Show her in. And bring us some tea.”

Nothing else could have relaxed Molly the way the mention of tea did. Tea was a civilized drink. A drink that people took time to consume. Tea meant at least a quarter hour of Mr. Gilchrist’s time.

She rose at the same moment the secretary reappeared in the doorway. The older woman offered Molly a tremulous smile. “Mr. Gilchrist will see you now, miss.”

“Thank you.” Molly adjusted the purse at her wrist, briefly touched the locket resting against her chest, lifted her chin, and pasted on a confident smile. She knew she wasn’t much to look at, but a smile went a long way to making a plain person attractive. At least, that’s what her schoolteachers had told her.

Molly entered the office to find Mr. Gilchrist already on his feet, standing beside his desk. Had she not heard the man’s shouting moments before, she wouldn’t have guessed that he had a temper at all. He was her same height, which wasn’t overly impressive for a man even if it was unfashionable for a woman to be five foot six in her stockings. And Molly wore heeled boots that gave her two more inches on the man. But he was built like a bull, with wide shoulders and forearms that made the sleeves of his jacket strain against them. He had dark hair and a large handlebar mustache. He wore a lemon-yellow bowtie and a kind smile.

“Miss McKinney. A pleasure to meet you.” He held his hand out, and Molly offered her own. She never knew whether to expect a firm handshake or a bow, and most men didn’t seem to know which was best when greeting a female reporter. Mr. Gilchrist went up in her estimation with his offer of a handshake. “Please, have a seat.”

Molly thanked him and took a seat on the leather chair across from his desk while he made his way back to his own chair. “Thank you for agreeing to see me, Mr. Gilchrist.”

“How could I say no when you included an introductory letter from J.S. Wood?” Gilchrist folded his hands on his desk. “He called you a promising young mind, you know.”

The letter of introduction Molly had obtained from Mr. Wood had been sealed. She hadn’t any idea what he had said of her, but the glowing praise gave her courage another boost. “That is most kind of him.”

“He’s a good fellow, of course. A man with more of a mind for helping people around him than helping himself. I’ve noticed he has a real eye for people. I’ve read articles and editorials written by him for years, and my wife and daughters read aloud from his Gentlewoman magazine every time it comes into our house.” He shook his head slightly, and in a single blink, Molly could imagine him sitting in a room before a fire with a wife reading to him. “But I imagine you didn’t come to talk about Wood.”

Molly curled her gloved fingers around the portfolio in her lap. “No, sir. I actually came to see about a job with your newspaper.”

His broad shoulders sank. “Oh?” His smile faded. “Ah, I see. Of course. May I ask what sort of job you were hoping for?”

Her hope of a fair hearing lessened. Whatever the man had expected her to say, this clearly wasn’t it. “I would like a position on your staff as a reporter. I am an accomplished journalist. I brought samples of my work to show you.” She held the portfolio up but hesitated to place it on the desk. “I have written a few pieces for The Gentlewoman.”

“Very well. Let’s have a look.” He held his hand out and she surrendered her work to him. He appeared no more cheerful than before. “I must warn you.” He put her portfolio down in front of him. “I have a full staff of reporters and several who work freelance and send things in from time to time. I’m not in great need of more journalists at present.” He flipped open the portfolio, and Molly held her breath.

She had put her best piece first. The one that meant the most to her. At the beginning of that year, she had visited Octavia Hill and interviewed the social reformer about her organization, the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. Molly had spent an entire day with the woman who many called a troublemaker even while others thought her a saint.

The interview had changed Molly’s life. The hours speaking to a woman with such a love for nature and people had shifted Molly’s perspective. Working for a woman’s publication had been a safe start for her. But she could do so much more.

And she wanted to see the world in all of its natural beauty.

The secretary came in and quietly put the tea tray on a table near Mr. Gilchrist’s desk. She made a cup for him, setting it at his elbow. She softly inquired after Molly’s tastes before handing her a cup, too. The woman gave Molly an encouraging smile before closing the door, which Molly returned with tightened lips.

“I read this when The Gentlewoman published it,” Mr. Gilchrist said quietly, as though to himself. Then he turned that article and went to the next without another word. Molly’s heart sank. Her best work, and he’d already read it and had nothing to say about it.

The teacup rattled in the saucer, so she lifted it off the plate to stop the noise. She sipped at the warm drink, letting it soothe her anxiety as much as warm leaf-water possibly could. Why had she let herself hope for more than what she already had? The world of newspapers and journals hadn’t opened to women until recently, and she still found herself elbowed out of the way by her male peers. If she didn’t ask for private meetings with the interesting people of the day, she didn’t get to ask questions at all.

Her kind-hearted teachers had warned her when she left school at seventeen. They’d showered her with gifts—beautiful writing pens, reams of paper, notebooks, and letters of recommendation—but they had not given her much hope regarding her prospects. Indeed, it had taken her three years to find a newspaper willing to print her, and even then they’d only allowed her to comment on fashion.

The Gentlewoman had been a dream come true when they’d hired her the day she turned twenty-two. Now, at twenty-five years of age, five years of journalistic experience under her hat, Molly hoped for so much more.

“I notice you use initials in all your work,” Mr. Gilchrist said, turning another article over. “M.E. McKinney. Why is that?”

She returned her teacup to its saucer. “That was under Mr. Wood’s advisement. Even while writing for a publication meant for women, the thought is that using my initials will make readers take me more seriously. Most assume I am a man when they read my work.”

Mr. Gilchrist snorted. Then he picked up his teacup and sipped, his large mustache twitching the whole time. “I told you I have daughters. Two of them. Their mother was a governess before we met. A dying breed, I’m told. She’s well educated, and so are our girls. They’re thirteen and eleven. The eleven-year-old fancies herself a newspaper woman. Mrs. Gilchrist and I often wonder what we should tell her. Do we encourage her, because we can see women making steps in the world of newspapers—there’s even that lady editor now. I’m sure you’ve heard of her. Or do we tell her to become a teacher? Or a nurse?” He gave Molly a sad sort of smile. A commiserating smile. It finished off the last of her hope that the day would end as she wished it.

Still, she addressed his question with a sympathetic tone. “I imagine it is difficult as a parent. My teachers walked that line, too. They all told me I had a great talent for writing, but everyone stopped short of encouraging me to make a living from it.”

“What do your parents think of your work?” He put his cup down and tidied up her portfolio. A precursor to him closing it and handing it back.

“I hope they’re proud of me. Though I don’t know what they would think. They passed away when I was quite young.” She forced a smile, the one that told people it was an old wound that didn’t quite hurt anymore.

Mr. Gilchrist’s mustache stopped twitching. “Oh. I am sorry to hear that.”

She placed her saucer on his desk, the cup rattling until the moment she released it. She wouldn’t cry. She refused to cry. How many times had men sneered at her vocation and told her a woman was far too delicate, too emotional, for such work? Crying only proved them right. Men certainly didn’t cry on the job. At least, not that she had seen.

And Mr. Gilchrist was being exceptionally kind. Somehow, though, that made it hurt even more.

The editor closed her portfolio and held it out to her. “Your article on the National Trust was interesting. I thought so the first time I read it, too. My wife thought I should have one of my men cover the story after she read what you said, about the responsibility we hold to safeguard natural beauty for our children. We were both quite moved.”

Molly nodded her thanks and held the portfolio close again, feeling rather like a child clutching a favorite doll for comfort. Would Mr. Wood be disappointed when she returned to her desk at the magazine with the news that she was unwanted elsewhere? Perhaps he would second-guess her place with his staff of writers, too.

“I wonder.” Mr. Gilchrist tipped his head to the side, his bushy eyebrows coming together as he studied her. “If you worked at this paper, what would you hope to write? Society pieces? Fashion advice? Or perhaps a column for women’s suffrage?”

“If that was what my editor wanted.” She smiled, then laughed at herself. Why not confess her dream? She wasn’t going to get it. “If I could do anything I wanted, I would ask for a position as a traveling reporter. I would love to go places that most in London, or in England itself, will never see and write about those places. That way, everyone might know what Niagara Falls in Canada looks like, or whether there really are alligators the size of trams in the swamps of Florida. Perhaps I would write a piece on the American West—about the cowboys and Indians that fill our novels here. Do they still exist? Are they still at war, as our fiction would have us believe?”

“Fascinating ideas.” Mr. Gilchrist stood, and Molly did the same. “But I’m not certain our readers would care for those things.”

Molly reached for his hand when he offered it, knowing the interview was over. “You have a fine paper, Mr. Gilchrist. I hope you find what you need for those readers. The thing they come back for, week after week, that they can’t get anywhere else.”

He blinked at her, perhaps surprised she remembered what he had said to his staff or that she had heard him at all. “Yes. Thank you.”

Molly stepped away from his desk, promising herself not to shed a single tear. Not until she made it outside to the pavement. She had only gone a few steps, however, when Mr. Gilchrist called her back.

“Miss McKinney? I beg your pardon, but I wonder—what does M.E. stand for?”

She looked over her shoulder at him, one hand on the doorframe of his office. “Mary Elizabeth.” There had been so many Marys, Elizabeths, Beths, Pollys, and so forth in the school for girls where she’d ended up that her teachers had settled on calling her Molly, and so she had been from the time she was nine years old.

Mr. Gilchrist held his hand out to her. “Wait a moment, Miss McKinney. Please.”

She stood frozen, half in and half out of his office. “Sir?”

He came around his desk. “Perhaps I was too hasty before. You see, I’m not a superstitious man. But I do believe in signs. That’s why I asked Mrs. Gilchrist to marry me, you see. A sign. And it proved a good choice.” He tugged on the lapels of his coat. “Our daughters are called Mary and Elizabeth.”

Molly blinked at him, hardly believing that a man in his position would give heed to something so simple as a coincidence in names. “How lovely.” What else could she say?

The editor smiled, and his mustache turned up at the corners, too. “Maybe you better sit down again, Miss McKinney. Tell me more about this idea of yours. A traveling reporter, you say? How would such a thing work?” He gestured to the chair, and Molly’s hope rose like a phoenix from the ashes.

Her dream hadn’t died yet.